The MingKwai Experiment: Typing Chinese Before Computers

One year ago, American couple Jennifer and Nelson Felix discovered a peculiar typewriter in boxes cleared out from Jennifer’s late father’s Arizona basement. The characters on its keys appeared to be Chinese. Wondering whether it might be valuable and unable to find any sales listings online, they posted about it on Facebook.

They couldn’t find any sales records because, as they later discovered, the item they had found was the only one of its kind ever produced: It was the long-lost prototype of the MingKwai typewriter, an invention that fundamentally redefined the logic of typing Chinese characters.

In the year since its discovery, the MingKwai has been an object not just of curiosity, but of intense study by academics and other researchers, including myself and my collaborators. Where we once had only old patents and other documents, we now have images of a real, physical typewriter. Its ingenious design, based on a statistical study of the Chinese language, influenced today’s digital input methods for Chinese and also shows an alternative reality of what our computers might have looked like today had their developers not used the Latin alphabet.

The MingKwai’s inventor was Lin Yutang, a celebrated Chinese novelist and scholar living in the U.S. who, after earning substantial royalties from his 1930s bestsellers “Moment in Peking” and “The Importance of Living,” poured his entire fortune into an obsession.

In the first half of the 20th century, the global explosion of information was accelerated by new technologies such as the typewriter and the telegraph. But Chinese, with a writing system consisting of tens of thousands of characters, proved difficult to fit into a technological framework first invented for the Latin alphabet’s mere 26 characters.

Chinese typewriters did exist, but they were clunky machines, requiring typists to hunt through large trays of thousands of individual metal types or to punch in memorized four-digit telegraph codes. For years, Lin withdrew into his study, sorting Chinese characters and sketching drafts, in an attempt to build a Chinese typewriter that could accommodate tens of thousands of Chinese characters while remaining intuitive enough for general use.

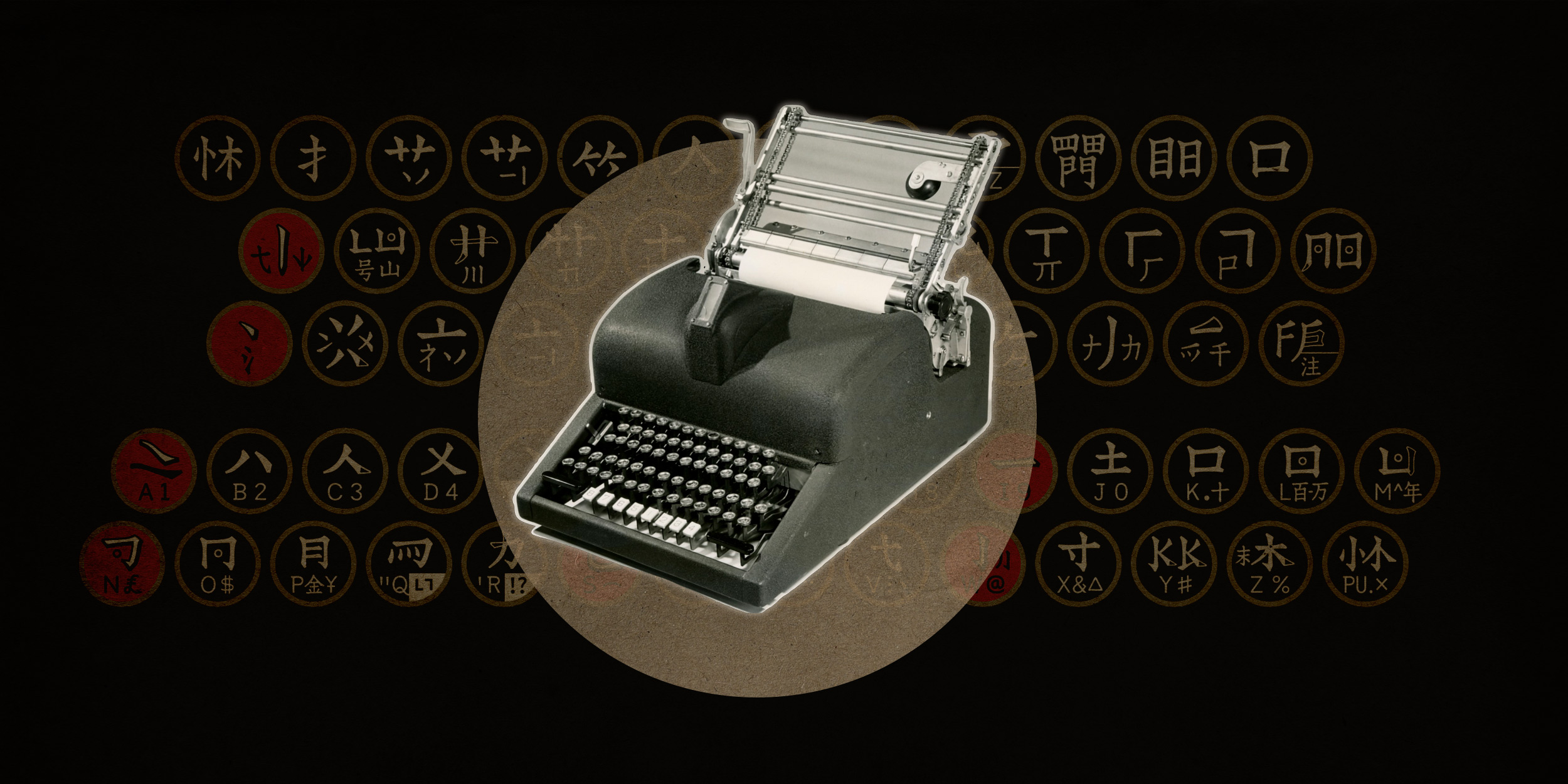

In 1947, at a media event organized in his home, Lin unveiled the machine he named MingKwai, meaning “Clear and Quick” in Chinese. Encased in a sleek black metal shell, MingKwai was unlike any existing typewriter. It was slightly larger and heavier, but most importantly featured a unique 72-key interface and a small viewing window right above it that offered a clever solution for Chinese “typing.”

On a Latin typewriter, what you type is what you get. Things are different for Chinese; no keyboard could ever include every character. To solve this problem, Lin invented what he called the “Two Corner” indexing method. The keys of MingKwai’s keyboard were labeled not with complete characters, but with deconstructed visual shapes that represented the top-left and bottom-right corners of Chinese characters.

A typist would use a three-keystroke sequence to progressively “locate” the character they were looking for: First, press a key for the top-left shape of the intended character from the top three rows of the keyboard; second, press a key for the bottom-right shape from the bottom two rows; third, consult the Magic Eye viewing window, which provides real-time feedback by narrowing the search and displaying eight candidate characters, and then press a numeral key (1–8) to select and print the desired character.

The user could select either a full-sized Chinese character or combine half-width characters. Lin claimed this system allowed MingKwai to type over 90,000 characters, though our research shows that only about 31,000 of those combinations were actual characters in use.

This “type-view-select” workflow is the same cognitive loop used by hundreds of millions of people on smartphones and computers to type Chinese. Unlike most modern input methods, which rely on Pinyin and require knowledge of Mandarin pronunciation, MingKwai made Chinese typing a purely visual exercise. This made it accessible even to speakers of different dialects or even to those who did not speak Chinese at all.

Recognizing MingKwai’s novelty and usability, and the immense potential of the Chinese market, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, then a dominant force in the printing world, purchased the machine’s patents and explored the possibility of mass production.

Commercialization never materialized, however, due to high manufacturing costs and shifting geopolitics in the 1950s. The prototype Lin had built with all his savings — and significant debt— was retained by Mergenthaler Linotype and later set aside somewhere by one of its employees.

MingKwai was forgotten for decades. Lin and his family never saw the machine again, nor did the wider world, until it was miraculously rediscovered in an American basement.

Although MingKwai existed for decades largely as a legend, and the prototype now sits under the protection of Stanford University Library, its inner workings are no longer a mystery. Lin’s now-expired patents and other archival materials reveal the machine’s basic structure: About 7,000 full- and half-width characters arranged on 36 octagonal bars that move according to user input. They are controlled by a highly intricate mechanism developed by an engineer Lin hired.

The bigger secret of MingKwai, however, lies not its marvelous mechanics but in its character arrangement, which directly determines how characters are retrieved through keystrokes. It had to be meticulously crafted: each key combination had to yield just the right set of candidate characters without wasting the machine’s limited type capacity. Achieving this required deep statistical analysis of Chinese characters and years of iterative experimentation —a process that occupied Lin for decades.

Evidence of this arrangement survives in a document called “The MingKwai Typewriter Model,” preserved at the Lin Yutang House in Taipei and recently digitized. It comprises 36 character tables corresponding precisely to the machine’s 36 bars, showing how characters were distributed under Lin’s plan. Using this material, my colleagues and I were able to reconstruct the typing system he devised.

When arranging the characters, Lin did more than simply assign them to keys. He organized them by frequency of use, ensuring common words required fewer keystrokes. He even included user-oriented features: terms for formal correspondence, “ditto” marks for efficient listing, and convenient shortcuts for rapidly inputting numbers and punctuation.

More surprisingly, MingKwai could handle multiple writing systems. It included a full set of Latin letters and Arabic numerals — in both upright and sideways-rotated forms to support the vertical typesetting conventions common in mixed-script texts. The machine could also handle Cyrillic and Japanese characters, along with Zhuyin (Bopomofo), the Chinese phonetic system used at the time. In effect, Lin built a multi-script workstation.

This was a remarkable feat for its era. Even early computers could not process multiple writing systems simultaneously before the turn of the millennium. Information technology ultimately developed around the Latin alphabet, forcing manufacturers to modify machine designs or even its entire structure when expanding into non-Latin markets.

This does not mean Lin envisioned “script inclusivity” in a modern sense. It is more historically sound to view MingKwai’s embrace of multiple scripts as a product of unintentional genius. Lin was solving the needs of office work in a globalizing world. For a machine already capable of housing about 7,000 characters, adding a few hundred more posed little difficulty.

Sadly, the world offered little opportunity for mechanical Chinese typewriters. What followed were computers — also designed around the Latin alphabet — which still had to address the problems of storing and retrieving Chinese characters. In the 1960s, disappointed by Mergenthaler Linotype’s inaction, Lin partnered with IBM on translation technology, developing a Chinese-English translating machine based on the same Two-Corner indexing method. The technology was later licensed in the 1980s to a company in Taiwan to develop Chinese computers.

Though MingKwai never achieved commercial success, its influence endured. According to Thomas Mullaney, author of “The Chinese Typewriter” and a key figure in ensuring that the MingKwai prototype was preserved at Stanford University Library, “MingKwai marked the birth of ‘input.’” Whether through visual retrieval of Chinese characters or through the concept of combining keystrokes to “input” them, these approaches laid the foundation for early Chinese digital input methods.

Lin Yutang’s dream of a machine for “everyone to use” has become reality — not in a heavy black metal case, but in a small one carried in the pockets of billions.

Du Xiyao contributed to this article.

(Header image: Visuals from the public domain, Liu Yuli, and VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)